Social Cues: Why Do So Many Snooker Players Put 147 In Their Handles?

Does putting "147" in your social media handle make you a better player, and can we predict who does it based on their playing career?

Snooker loopy, data groupy

Every April I go snooker loopy. For two and a half weeks during the World Snooker Championship, I’m glued to the sofa by 7pm sharp to watch Rob Walker introduce the players, yelling “where’s the cue ball going?!” any time there’s a whiff of danger in the opening frames, before inevitably dozing off to the gentle click of balls during a late-night safety exchange.

The problem is, once the final ball is potted and the Crucible lights go down, I ignore snooker for the other 49.5 weeks of the year. So this year, I thought I’d give something back. Not with anything useful, like some of the other great snooker data projects (snooker.org, CueTracker, or the Expected Pot metric, to name a few), but instead by investigating why so many players have “147” in their social media handles.

If you’re not fluent in snooker-speak, don’t worry, this will only loosely be about snooker, and I think I’ve somehow uncovered some (very mildly) interesting data around social media usage in sport (yes, SPORT). In snooker terms, there are just two key things you need to know to get up to speed here:

Snooker has a “perfect score”, a bit like a hole-in-one in golf or a nine-darter in darts. That perfect score is 147, and I’ll explain what that means shortly.

Snooker players are unusually online. Unlike athletes in more heavily media-trained sports, many are surprisingly active on X (formerly Twitter). And if you scroll through their usernames, you’ll find that a lot of them choose to include “147” in their handles.

This got me thinking: is having “147” in your handle an earned badge of honour, like a nod to say “yes, I’m amazing at this”, or just a cheap neon sign saying, “I play snooker”?

What is the 147?

For the uninitiated, here’s a quick explanation of the 147, brought to you by me on Christmas Day 2008, proudly breaking off on a brand new miniature snooker table (not quite regulation size, and limited to 10 reds instead of 15). To help, I’ve labelled the balls with their point values.

Players score by potting a red (1 point), then a colour (ranging from 2 to 7 points), then repeating that red–colour sequence until the reds are gone. After that, they pot the remaining colours in order of value.

A “maximum break”, or 147, is when a player pots 15 reds and 15 blacks (the highest-value colour), then clears all six colours. I’ll save you the maths, it totals 147. That’s the highest possible break without any fouls or free balls. For reference, here's Ronnie O'Sullivan doing it in just over five minutes.

Lots of snooker players put 147 in their X handle

The idea of a “perfect score” isn’t unique to snooker, but I’m not sure any sport flaunts its magic number on social media quite like snooker does. Rory McIlroy’s handle isn’t @RoryMcHoleInOne, and while plenty of darts players go with “180”, it’s not really comparable, those happen all the time.

There are, however, LOADS of snooker players that have put 147 in their social media handles. To be precise, on the platform formerly known as Twitter, there are 62 professional snooker players on record (past and present) with a handle that includes “147”. So, is this just basic branding? A way of signalling “I play snooker”? Or is there something deeper going on?

Before going any further down the rabbit hole, I should acknowledge the amazing work that Hermund Årdalen is doing with snooker.org and its brilliant API, without which obtaining the data for this work would have been a lot more tedious (read: it wouldn’t have happened). Also, quick disclaimer. I’m aware that all of these pro snooker players have probably made a jillion 147s each in practice/non-professional matches. This is all just a bit of fun, and a celebration of my love for snooker. Just getting ahead of any Reddit comments like this one calling for me to be “gulaged” following my last article.

Onwards.

I pulled snooker.org data for every pro player on record, including their X handle where available. From there, I mapped out the relationships between a few key groups: players not on X, players on X, players with a recorded 147, and players with “147” in their handle. These relationships can be seen in the Euler diagram below.

If you’re not familiar with Euler diagrams, they are to Venn diagrams what Jamie is to Andy Murray: almost identical with a similar skillset, but best utilised in slightly different settings. Each area in an Euler diagram is proportional to the size of the group it represents, but unlike a Venn diagram, not all possible intersections are shown, only those that actually exist in the data. So if two sets don’t overlap in the diagram, it’s because no one falls into both (e.g. “Not on X” and “On X” cannot overlap, and “147 in Handle” has to be entirely self-contained within the “On X” set).

Towards the top, we see that most players (198 out of 342) aren’t on X (understandable). But among those who have made a professional 147, most are online (44 on X versus 29 not). Makes sense: the top players are more likely to have a brand worth building (more on this later).

Now for the best bit. Of the 62 players with “147” in their handle, only 21 have actually recorded one in pro play. Shockingly, this means that if you are a snooker player with “147” in your handle that has actually scored a 147 in pro play, you are in the overwhelming minority.

At the bottom of the diagram, I’ve zoomed in on two key sets: players with a professional 147, and those with “147” in their handle. Some standout names with “147” in their handle but none on record: Chris Wakelin (World No. 16, recent World Championship quarter-finalist), Elliot Slessor (No. 29), and the recently banished Mark King (career-best ranking of 11).

Does having 147 in your handle actually mean you’re worse?

Interestingly, most players who have made a 147 don’t put it in their handle (playing it cool?), and most of those who do include “147” haven’t actually made one (manifesting?). So does putting “147” in your handle actually make you less likely to score one? The raw numbers suggest something’s up, but I wanted to test it more formally.

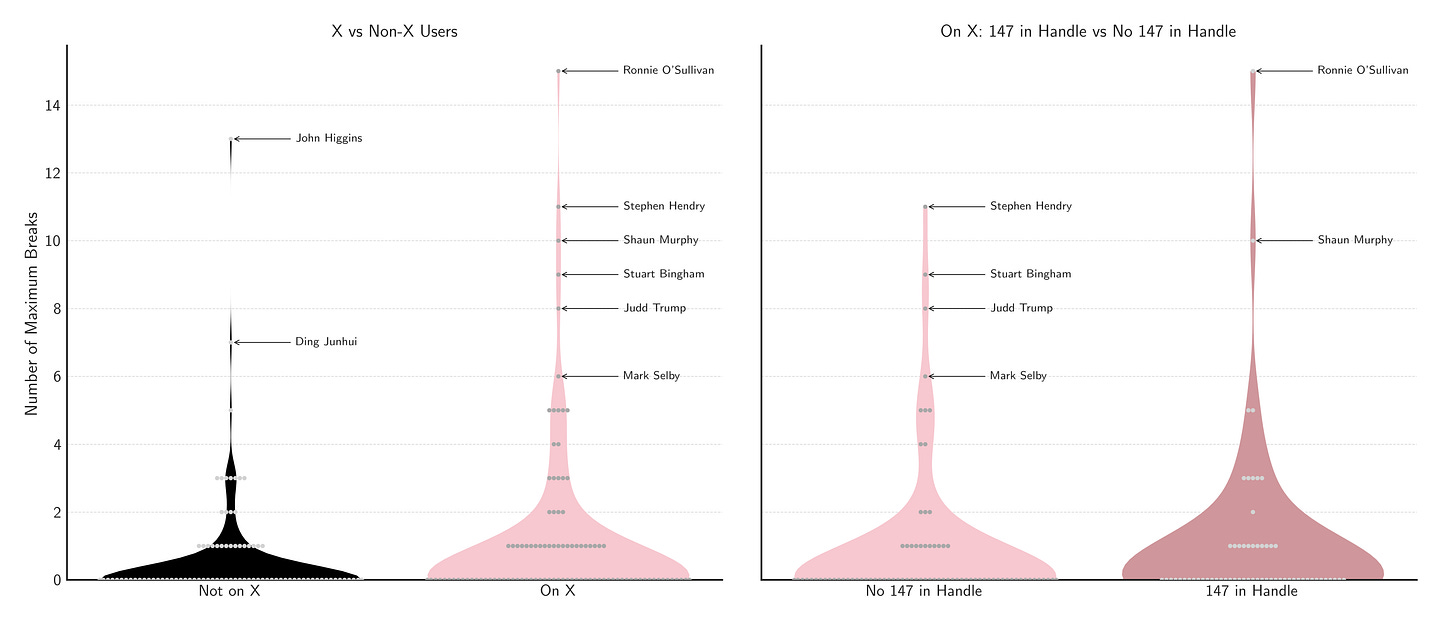

Below are violin plots showing the distribution of players’ maximum break counts. On the left, split by whether they’re on X, and on the right, by whether their handle includes “147”. Both are heavily skewed: most pros have never made a 147, and even among those who have, one or two is the norm.

To dig deeper, I ran some tests. For binary yes/no comparisons (e.g. ever made a 147 or not), I used chi-squared tests. For comparing break counts (which are non-normally distributed), I used Mann–Whitney U tests: a non-parametric way to compare groups without assuming a nice normally distributed bell curve. The results:

Players on X are more likely to have recorded a 147 than those not on X. This difference is statistically significant (χ² = 11.64, p = 0.0006), and is also reflected in the distribution of maximum breaks (Mann–Whitney U = 16584.00, p = 0.0003).

Among X users, there is no evidence that having “147” in your handle is associated with achieving one. Both the chi-square test (χ² = 0.32, p = 0.5698) and the Mann–Whitney U test (U = 2671.50, p = 0.5222) suggest no meaningful difference between those with and without “147” in their handle.

So, yes, being on X is more common among the game’s elite. But sticking “147” in your handle? Doesn’t make you any more (or less) likely to pot 15 reds and 15 blacks under the lights. If anything, it’s just a bold bit of personal branding.

Being online is earned

If having “147” in your handle isn’t about having a 147, then what is it? Using data from snooker.org for 342 professional players, I built models to predict two things:

Whether a player has an X account.

Whether, if they do, their handle includes “147”.

With a relatively small dataset (342 players in total) and a preference for interpretability, I focused on a few traditional machine learning algorithms. These included logistic regression, decision trees, and random forests, all of which offer some insight into how individual features contribute to the model’s predictions. The input features covered a range of player attributes, including age, nationality, number of professional seasons, number of ranking titles, and total 147s.

First up: predicting whether a player is on X. This turned out to be fairly learnable on the limited set of features provided, with logistic regression performing best, hitting 65% accuracy on the test set. Not groundbreaking, but better than chance. It correctly identified 21 of 29 X users and 24 of 40 non-users. While far from perfect, this is a respectable result given the limited data and binary nature of the task.

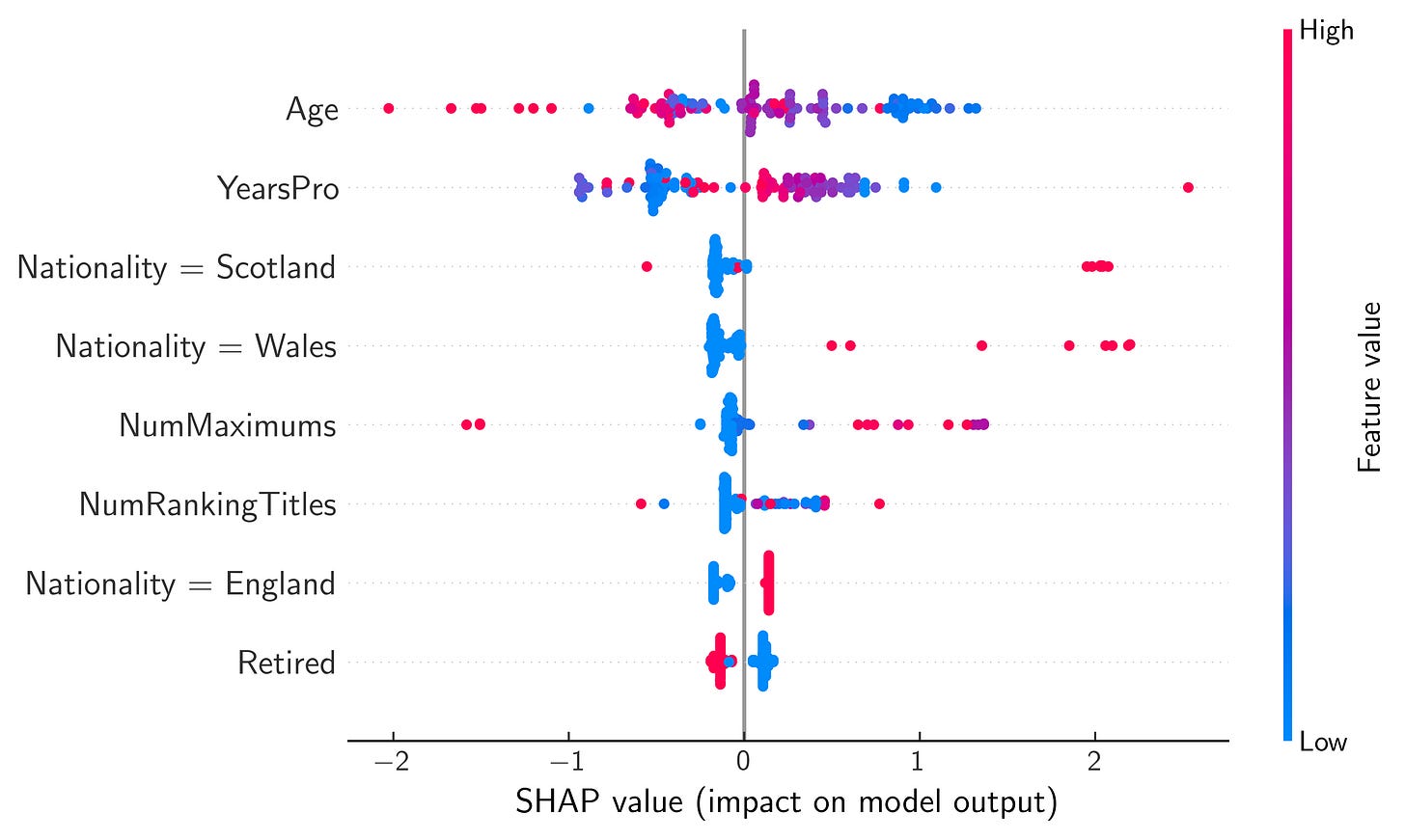

To understand why models made certain predictions, I used SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to estimate feature contributions for consistency across models. The SHAP summary plot below shows that nationality, age, and having a maximum were the most influential factors. Each point represents a player, and each row corresponds to a different input feature. Points to the right indicate a higher contribution toward the player having an X account; points to the left suggest a push toward not having one. The colour of each point reflects the feature’s actual value: red for high, blue for low.

So, for example, a blue dot on the “Age” row (i.e. a younger player) appearing on the right means youth is nudging the model towards predicting that the player is on X. For binary features like “Nationality = China”, a high value (1) means the player is Chinese, while a low value (0) means they are not.

Players from England were also more likely to have X accounts, while players from China were much less likely (I’d imagine X being banned in China is probably quite important here). Years as a professional and whether the player is retired also had consistent directional influence, suggesting that being an active and established pro correlates with platform presence.

I suppose the results are exactly what you’d expect. More experienced pros, who’ve achieved more in the game, but are young enough to be internet savvy, are more likely to have an online brand. And maybe something to sell. Three of the top four players with the most 147s are on X: Ronnie O’Sullivan, Stephen Hendry, and Shaun Murphy. Ronnie sells the Rocket Method; Stephen and Shaun have active YouTube channels and merchandise lines.

John Higgins, if you’re reading this, you’re leaving money on the table.

If in doubt, just put 147 in your handle

But what about putting “147” in your handle? I trained a second model (using the same input features) to predict whether a player on X included “147” in their username. This turned out to be much harder to pin down. Of the algorithms tested, gradient boosted decision trees performed slightly better than the rest, but only just.

The confusion matrix tells the story: the model correctly identified just 3 out of 12 players who actually had “147” in their handle, and misclassified 9. It did a bit better at spotting those without it (13 out of 17), but overall, predictive power was extremely limited (16 out of 29 correct predictions).

The SHAP plot backs this up. While features like age, nationality, and years as a pro had some influence, the effects were inconsistent and messy. Even the number of maximum breaks (a stat you’d think might matter) didn’t show a strong or reliable association. This supports the statistical analysis earlier: players who include “147” in their handle don’t necessarily make them, and those who do make them don’t tend to base their brand around it.

In short: self-branding as a 147-hitter appears to be largely independent of measurable career success, at least with the limited data I had available. The model couldn’t find a reliable pattern, and perhaps there isn’t one to be found.

Sorry snooker, see you next April.

sensational