You probably aren't the next Jamie Vardy

Football's age curve provides a quick statistical reality check for any grown adults clinging to hope of a career as a professional athlete.

This was supposed to be something light-hearted about how careers in some sports last much longer than others. Then I started writing and it all went a bit miserable when I realised what age I am.

The next article will probably go back to something more cheerful. Christmas spirit and all that.

Quarter-life crisis

At some point in the next six months I’ll submit my PhD thesis. This will effectively end a 20-plus-year streak of being continuously enrolled in some form of full-time education.

Because of this unavoidable career crossroads, brought on by a long sequence of choices made with varying degrees of information and rationality, I’ve recently found myself sitting around staring at walls more than usual, wondering what to do next.

I’ve never really liked the phrase “quarter-life crisis” as a description. It sounds like its probably something from pop-psychology, something an older generation would roll their eyes at. “Back in my day we just had a mid-life crisis.” But after doing some research (reading the first paragraph of the Wikipedia entry), I do feel that it fits annoyingly well.

And being a football fan really isn’t helping. As Michael Caley bluntly put it in Expecting Goals:

“Anyone can observe that the vast majority of professional athletes are young adults.”

On the surface, professional footballers are life’s winners. They’re successful, adored by millions, and have built entire careers out of being good at kicking a ball. They’re also disgustingly rich; most of these twenty-somethings will make more in the next few months than I’ve made in my entire life.

The age curve

The annoying reality is that my opportunity to pivot into a professional football career has passed. Even if you suspend disbelief long enough to ignore my lack of talent, dedication, or fitness, I’m simply too old. Sports analytics has a well-established concept called the age curve, which (as far as I can tell) Michael Caley first introduced to football in 2013.

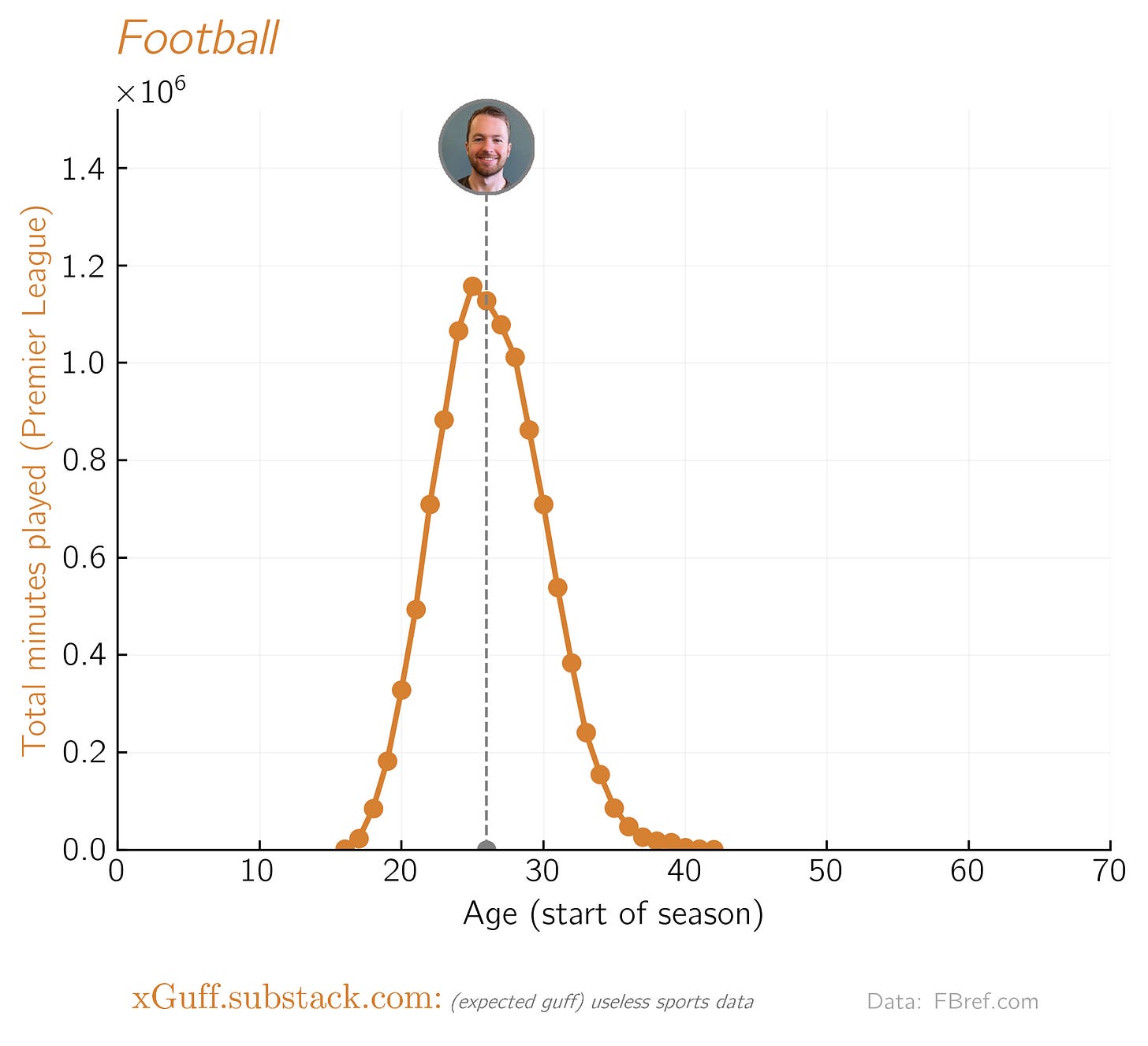

The basic idea is simple: plot some measure of performance (minutes played in high-quality leagues are generally a good proxy) against age, and look at the distribution.

When you do this for Premier League minutes over the past 15 seasons, the curve looks like this:

You’ll notice I’ve annotated where I sit currently. Having turned 26 at the start of this season, I am now officially past the expected peak age of a Premier League footballer.

The Vardy fallacy

“Don’t give up! Jamie Vardy didn’t play in the Premier League until he was 27! He’s still playing in Serie A aged 38!”

This is true. But even Vardy, the poster boy for “it’s never too late,” had a professional contract at Halifax Town at 23 and a Championship move by 25. I, on the other hand, have not played an 11-a-side match in years. The highlight of my football CV is a small handful of Footy Addicts “Player of the Game” awards.

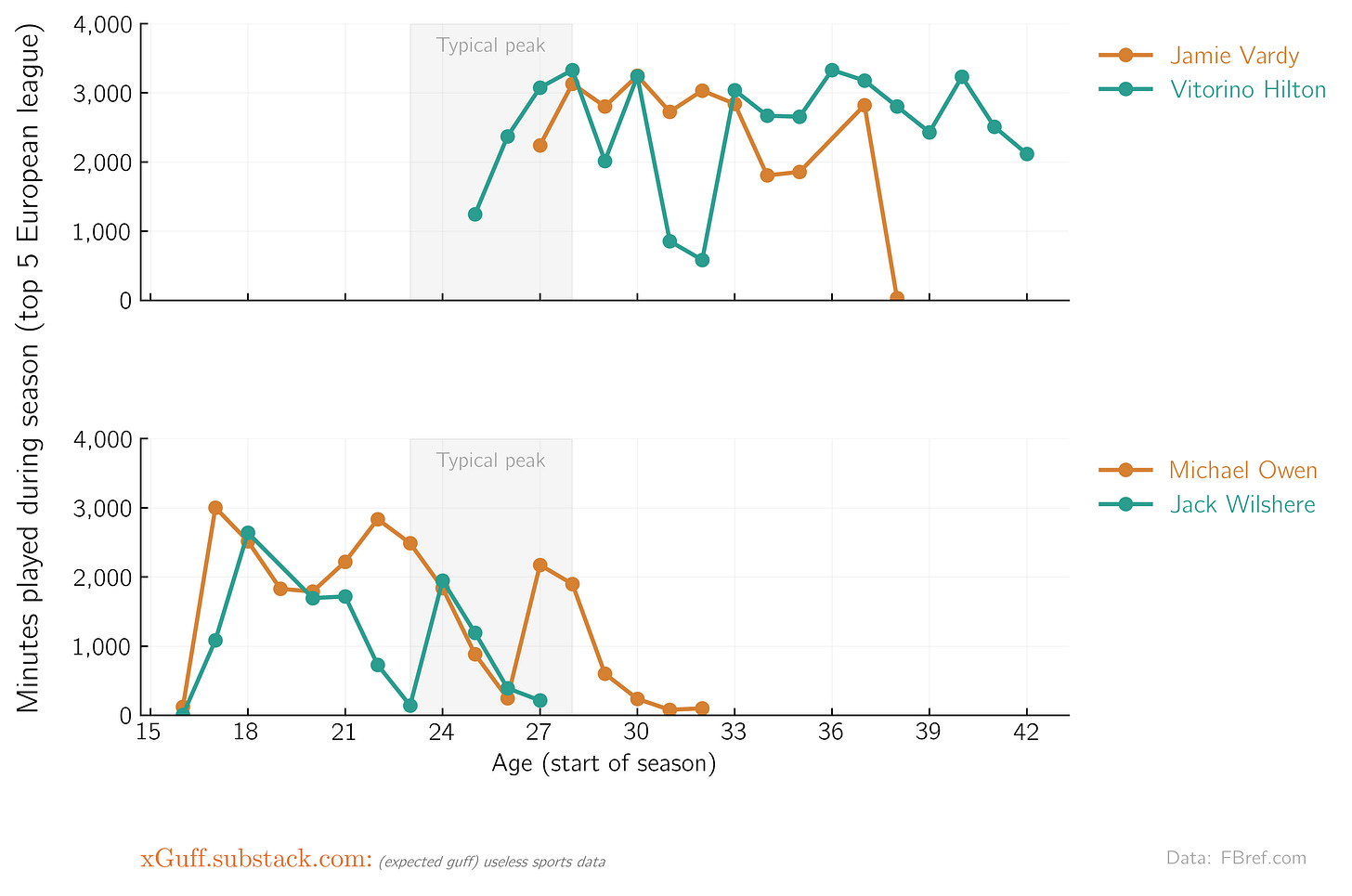

While the underlying distribution of football age curves is long-tailed (roughly meaning the probability of rare late bloomers remains non-zero but tiny) there are also examples at the other extreme. Below are individual curves for a couple of late bloomers (Jamie Vardy and Vitorino Hilton) and a couple of early peakers (Michael Owen and Jack Wilshere):

Each of these players is a statistical outlier in their own right. So when you aggregate all player across many seasons, their unique stories get lost, swallowed by the overwhelming mass of 23- to 28-year-olds operating at laboratory-grade peak performance.

This is the ruthless nature of the probability curve. While we love to focus on the stories produced by the long tail, where the miracles like Vardy live, statistical reality is governed by the fat, undeniable middle.

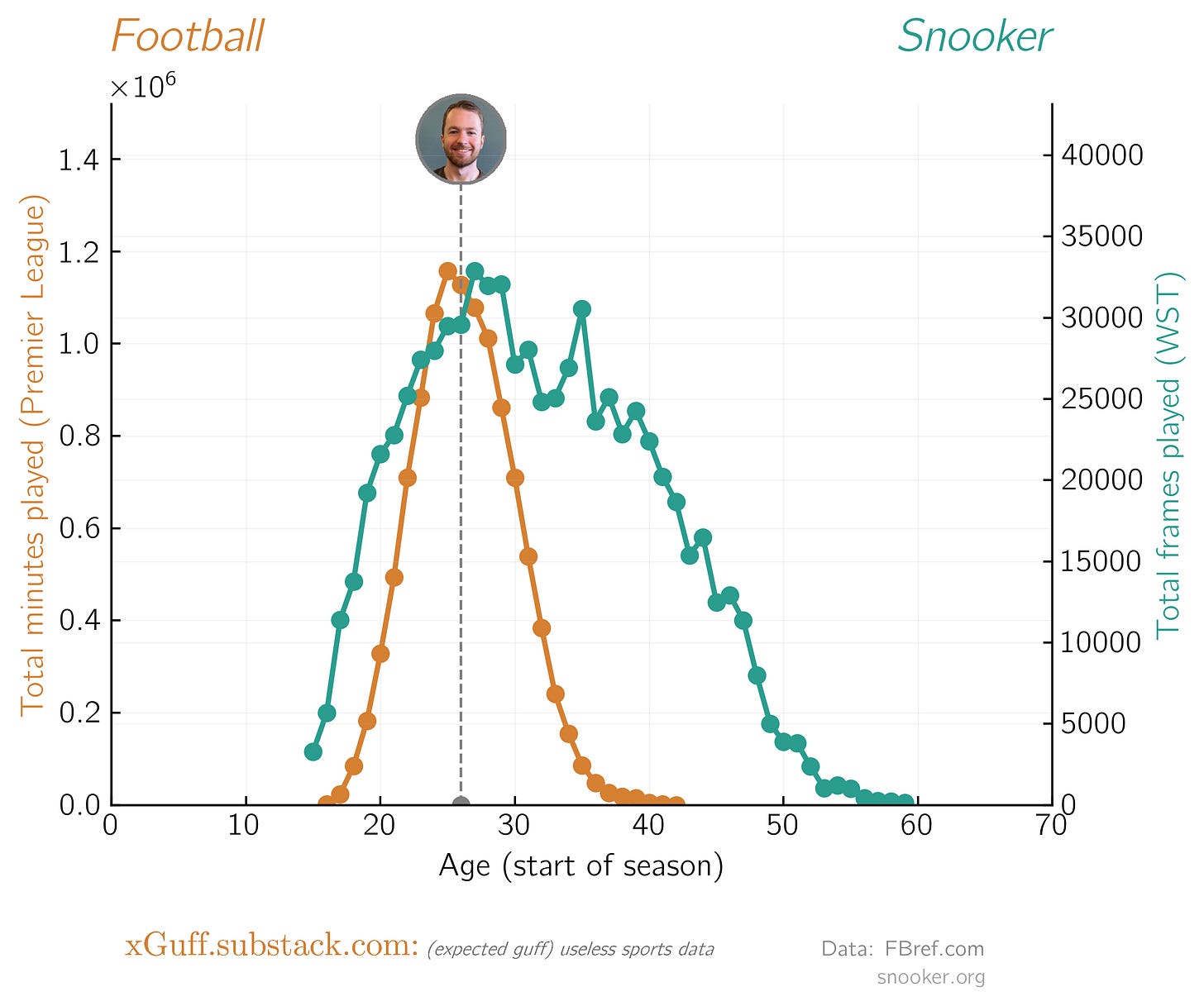

Clutching at straws, I turned to a sport whose competitors are often thought to enjoy much longer careers: Snooker. A sport in which professional players were actively boozing and smoking their way through matches until as recently as the 2000s. Maybe the distribution is on my side here. After all, three of snooker’s current top 10 in the world turned 50 this year (O’Sullivan, Williams, Higgins).

Although I’m not quite at the peak age for frames played on the World Snooker Tour, I’m only about a year off. The distribution is similar to football’s, just shifted slightly later and stretched out a bit. But the message is the same: time is no longer on my side.

Conclusion

The statistical truth is sadly unavoidable: we’re all just numbers in a large, boring underlying distribution. Most of us fall somewhere near the middle.

I don’t get age demographics for my readership, but I suspect a decent number are hovering somewhere around the same stage in life. So if you’re in a similar boat, harbouring a similarly far-fetched dream from childhood, I’m here to tell you it’s over.

If you wanted to make your millions playing football, you should have put a bit more serious thought and preparation into that when you were a toddler. It’s too late now.

Give it up. Embrace the mediocrity. Welcome the mundanity.

And yet, the probability that there exists another Jamie Vardy out there is what keeps the game interesting.